Culture Struggles

- Connor Gerrity

- Sep 15, 2024

- 8 min read

Galizia, late 19th century - Vienna, early 20th.

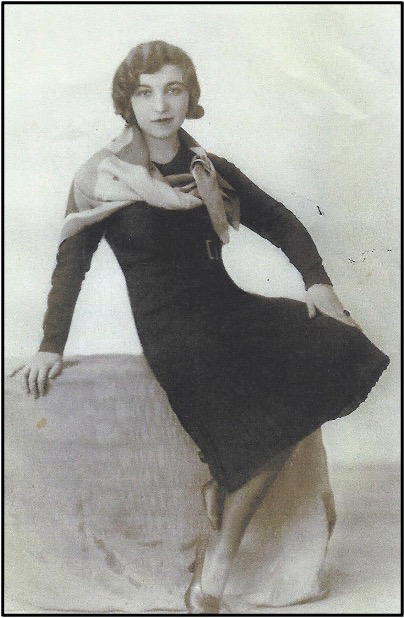

After I came to the US in 1968, my grandmother gave me a photo of Mom in Vienna, ca. 1924. It is a formal portrait that exudes beauty and elegance. There’s not a trace of the Ostjud in her. She has become a sophisticated Viennese in high heels, a fashionable dress, and a marvelous silk shawl draped over her shoulder. Her hair is combed in a Marcel wave. She looks like Marlene Dietrich posing for a movie shot.

___

As I told you in Blog 13, Two Portraits of Mom, the seven intervening years between Mom’s and Dad’s deaths had not been good ones. My relationship with Dad deteriorated, my maternal grandmother Omi, went to the US in 1963 when I was fourteen, I became rebellious, Dad became ill, and shortly after that, he passed away. At the end, our live-in maid Nilda and I were the only ones left in the Goldstein household. After fifteen years of living with us, Nilda had become a member of the family, and she witnessed our slow disintegration. The final act was no more than that of a sandcastle battered by one ocean wave after another until nothing was left but an amorphous mound.

A few months after Dad died in 1968, I gave away most of my folks’ possessions, packed my bags, and came to the US. It was with my—by then—entrenched stoicism and denial that I bade farewell to my dear Nilda on the day I closed our apartment and went to the airport. (Nilda quickly received another job, as she came highly recommended by all of my parents’ friends who knew her. I rented our apartment for a few years until I eventually sold it.)

I was nineteen and finally free of the losses and heartbreaks that had figured so prominently during my upbringing. My idea was to come to the US to study chemistry and restart my life—as though nothing had happened. Talk about denial.

Of course, I did not go to study in London or Berlin. I came to the US because Mom’s family was here: her mother, my Omi, and her brother, my Uncle Jack, as well as his wife Bertha. Their home was not in New York City proper, but across the Hudson River, in a high-rise apartment in West New York that had a gorgeous view of the Manhattan skyline. For all of us in Buenos Aires, however, I was heading to “New York,” that wondrous city in the Promised Land. I did not live with my folks in New Jersey but in the Rensselaer Polytechnic dorms up in Troy. For better or worse—mostly worse—I had inherited Dad’s stubborn self-reliance. I did not need anyone. I, and all the baggage I carried, could brave the hills of Troy by myself. It would still be a while before the baggage started rumbling.

Every now and then—not frequently enough according to my folks—I visited West New York. It was in these visits that I learned about Mom’s life before I was born. Talking about her was a chance I had never had with Dad. The tales I heard, of Mom, Galizia, Vienna, and the Second World War started filling some of the gaps that, because of Mom’s premature death, I had never heard in my childhood. Gaps that my taciturn father had never plugged.

The Mom I knew in my young years described herself as a Viennese. She sang and danced to Strauss’s waltzes, talked with passion about her Vienna, and painted a luminous picture of the city by the Danube. So, I thought of her as Viennese, at least until I learned better from my folks in West New York. The truth, like it always is, was subtler and more complicated. Mom wasn’t really born in Vienna; she was born in Lwow, Galizia, a city known today as Lviv, in Western Ukraine. In 1908, the year of her birth, Galizia was a Polish annex of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Omi had roots that went even deeper into Galizia. She was born in 1884 and raised in Rohatyn, a then shtetl of about 6,000 inhabitants. The whole of my mother’s family were Galizianers. Omi defined herself simply as, “from Poland.”

In 1914, at the beginning of the First War, Mom, then six years old, her younger brother Jack—so nicknamed after his recently deceased father Jacob—and their widowed mother Rachel arrived in Vienna. They were three impoverished refugees without a father. Together with tens of thousands of other Galizianers, they moved into Leopoldstadt. This was the Jewish neighborhood of Vienna's 2nd Quarter, which was overcrowded with Ostjuden, the Jews from the East. You may remember the differences between Ostjuden and Yekkes from Blog 26, Jewish Taxonomy. The men of Leopoldstadt wore long dark coats, not short jackets, like the Yekkes of Vienna’s more refined neighborhoods.

To the Galizianer immigrants, Vienna was their Promised Land. It was more than one of the great Kultur centers of Europe; it was the capital of the Hapsburg Empire and the home of Franz Joseph, the emperor whom Omi adored. She often praised him during my childhood in BA, remembering how under him the Jews had been emancipated. They could have any job and live anywhere they wanted, not just in the ghettos. She kept a picture of the heavily mustachioed Franz Joseph in her Vienna apartment and observed his birthday. The elderly Kaiser seemed to have been quite a figure in the fatherless household in Leopoldstadt. Mom also remembered him, although she was only eight years old when he died.

From the day Mom set her sights on the Ringstrasse, the central avenue of Imperial Vienna, she turned her head away from the shtetls of Galizia and became an urbane Viennese. Mom’s home in Leopoldstadt was a few blocks away from the Volksprater amusement park, which had, and still has, a giant Ferris wheel made famous by Orson Welles in The Third Man. Mom lived within walking distance of the Opera House and of the city's famous coffeehouses. The Vienna of my fantasies, put there by Mom’s own, was a city of luminaries. It was “Vienna Gloriosa,” as Professor George Berkley has called the city in his wonderful book, Vienna and Its Jews.

I imagine Mom as a young woman in her twenties, sitting at a marble table under the vaulted arches of the Café Central, enjoying a Kaffee and a slice of Apfel Strudel topped with a dollop of Schlag, the delicious vanilla-flavored whipped cream much favored by the Viennese. A Strauss melody is playing in the background while she is reading her way through the dailies and occasionally watching a heated discussion at a table a few feet away. Maybe it is Freud over there arguing with Adler about some case. Or Alma Mahler, Gustav's ex-wife, whispering to her new beau, the architect Gropius.

The other Jewish inhabitants of Imperial Vienna were the Yekkes. They had arrived in earlier years and had become genteel and Germanized. They were assimilated, and trusted that emancipation was the end of all their troubles. They did not live in Leopoldstadt, but in the mixed neighborhoods of middle- and upper-class Vienna. They were professors in the Medical or Law Schools, doctors, lawyers, and bankers. They belonged to families that had long ago left their religion behind, many having converted to Christianity. They spoke German—with an Austrian accent—but certainly not Yiddish. Yiddish, which they saw as a corruption of true German, was spoken only by the recently arrived Ostjuden, like my grandmother. The newcomers, with their Yiddish, their religion, and their men in ankle-length overcoats, stood out like sore thumbs in the imperial city.

The cultural struggles of Viennese Jews were as much about social class as about geographic origin. The struggles found their way into the family’s living room in Leopoldstadt. Omi was forever the Ostjud; Mom, with barely a memory of Galizia, aspired to be from, and belong in Imperial Vienna. When I knew all of them later in their lives, the only one who still spoke any Yiddish was Omi. Neither Mom in BA nor her brother, my Uncle Jack in West New York, spoke it, or at least wouldn’t be caught dead speaking it. I learned German from my parents in BA when I was a boy, never Yiddish. Well, as I have told you, Omi did teach me some anatomical words in Yiddish, like schmuck. To this day, my German has a distinct Viennese sing-song and subtle listeners may tell that I had a Viennese mother.

The cooking tastes of my mother and my grandmother in BA reflected the cultural split. Both of them knew their Viennese kitchen. Their Wiener Schnitzel, breaded veal cutlets with a slice of lemon and anchovy on top served with sweet and sour red cabbage, or their cucumber salad with dill dressing, were to die for. But what Omi ate as comfort food, and Mom didn't like, were shtetl dishes like cold borscht, a red beet soup with sour cream; or chicken giblets sautéed with schmaltz. My mother looked down on such dishes: "peasant food" she called them. Even my American wife Sandy, descendant herself of long-ago Ostjuden, thinks that giblets are the food of the hoi-polloi.

But a crispy Schnitzel followed by Strudel with Schlag are the tastes of the Vienna Gloriosa of my BA childhood. If the waltz Wien Wien nur du allein is playing in the background, the effect is complete. The food and the waltz are in my soul, and tears pour when I hear the famous melody, as though I too had left Vienna like Mom, and longed for it. Vienna has merged with Mom, and Mom’s longing for the city of her dreams has become my longing for the mother of my dreams, the one I lost more than sixty years ago, when I was a boy.

***

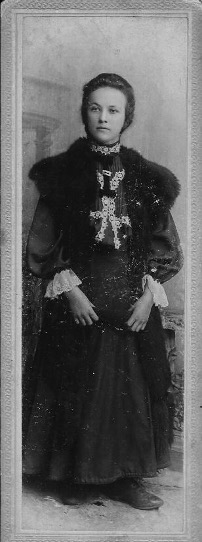

During our conversations in the early years of my arrival, Omi shared with me a box of photos of her youth. She encouraged me to take anything I wanted. I found there three wonderful pictures, one of Omi and the other of her husband Jacob. The pictures are from the early 1900s when they were still living in Lwow, Galizia:

Omi is wearing an ornately embroidered dress with a long-sleeved frilly blouse and, topping it off, what looks like a heavy fur stole. She looks regal, except for her incongruous shoes, which don't match the look. Grandpa Jacob is wearing a wrinkled uniform of unclear origin. Some historical research has led me to conclude that it was quite likely the uniform of the Polish Riflemen’s Association, which was formed in 1910 in Lwow. The Association gave paramilitary training to young Galizianer men in preparation for an expected fight against the Russians, especially the much-feared Cossacks. The Association was led by the socialist Józef Pilsudski, one of the great heroes of Polish independence. Grandpa Jacob died—apparently of malaria—before the First War, so he never got to fight the Cossacks. He sure cuts a romantic figure in his Riflemen’s uniform.

The third photo is that portrait of Mom that I told you about earlier, taken when she was sixteen years old, her Marlene Dietrich photo:

Mom, in contrast to her parents, looks like the sophisticated, urbane Viennese that she aspired to be. Not a trace of shtetl in her. Look at her left arm: it is not relaxed. I can see the effort she was making to keep it stylishly bent over her knee. Her formal pose is iconic of my Viennese mother.

The year that this photo was taken, 1924, Dad was emigrating from the Levant to Buenos Aires after the destruction of Smyrna. He was fifteen years older than she, and more than twenty years away from crossing her path.

Unfortunately, no amount of sophistication or emancipation could save Mom or the other Jews of Vienna, whether Ostjuden or Yekkes, when the Nazis came in 1938. The story of that darker Vienna is in my next blog: Vienna Dolorosa.

Comments