Looking for Old Smyrna

- Connor Gerrity

- Aug 5, 2024

- 7 min read

Izmir, 2014.

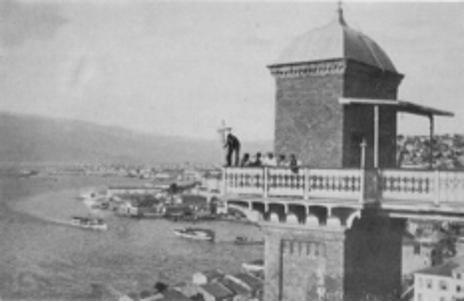

Our cab from downtown Izmir turned left from the seaside Boulevard Mustafa Kemal and started climbing up a hill toward Karataş, the old Sephardic judería of Smyrna. Halfway up the slope, we stopped in front of the Asansör, a structure so strange that I thought it was a buttress holding up the hillside. It is a narrow elevator shaft in the shape of a tall rectangular prism with a bridge on top connecting to the hill. It was built in 1907 and allowed the locals to effortlessly go up from the bottom to the top of the cliff. This elevator was such a novelty in the early 1900s that, whether he lived in Karataş or not, I’m sure that Dad – just like us that day - came out on a Sunday afternoon to ride the elevator and enjoy this wonder of the world. To the left is the Asansör in Smyrna and to the right, in Izmir.

Izmir – Old Smyrna - had been on my bucket list of destinations for years. I wanted to go there and dig ever deeper into my family’s past. I wanted to stand at the waterfront quay where, in 1922, thousands of desperate souls were caught between the fires, the soldiers, and the bloody waters of the harbor.

My wife Sandy and I finally visited the city in 2014, almost 100 years since Dad had lived there. I did a lot of homework before going. Dov Cohen, my Israeli sleuth and scholar, whom you met in Blog 21, “A Postcard from Constantinople,” had found the brothers Goldstein, Leon and Karl, in the city censuses stored in the Jerusalem archives. At different times Grandpa Leon was shown as owning a tobacconist shop or being involved in a clothing store that sold ready-to-wear apparel. Of bigger interest, the census showed that the brothers owned and ran an Austrian brasserie on the quay, next to the Grand Hotel Huck, a famous lodge in those days. I assume that an Austrian brasserie must have sold schnitzel, goulash, chicken paprika, and some good apfel strudel. These are the comfort foods I inherited in Buenos Aires from my Viennese Mom and from Omi, my maternal Grandma. Since both sides of my family started in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, I am not surprised that Dad had a healthy taste for these delicacies.

With the information about the restaurant and the Huck Hotel, another since-discovered cousin, South Africa-born Dave Lasker, went online. Dave is a descendant of my Aunt Cecilia, the one who married that freed soldier and settled in Liverpool. He found a hand-colored postcard of the Grand Hotel Huck and a city plan of the waterfront of Old Smyrna. The census records, the city map, and the postcard told us that the Grand Hotel Huck and the Goldstein brasserie next to it, sat directly on the Old Smyrna quay.

Below on the left is the old Smyrna postcard and next to it, my photo of what the Izmir waterfront looks like today.

In the early 20th century, the Hotel Huck, a three-story structure with an ornate façade, was flanked by two alleyways, both sporting striped awnings. Any of the awnings could have been, and probably one of them was, Grandpa’s restaurant. Looking at the modern waterfront, you wouldn’t know that this is the same place. For one thing the caravan of camels is no longer there. Neither is the Huck, probably having burned to the ground during the 1922 conflagration. In its stead and also with an alleyway on our right, there is another hotel, the Key, this one a modern four-story cube with a white façade and dark vertical windows. That’s where we stayed.

We spent our time trying to find as much of the Old Smyrna as we could. While difficult, it was not impossible, and with a bit of romantic imagination we managed. Like a passing reflection, we could catch sight of an old building here, or a statue there. The only way to make sense of these glimpses, surrounded as they were by the modern city, was to strain our eyes. We would try to erase all the visual noise and look at a spot as through a prism that is out of focus. That way, with the help of old postcards, we could rescue a few structures here and there.

Most of Old Smyrna has been erased, both literally by the destruction of 1922 and by history. There is a sort of benevolent nostalgia about it in the old postcards and Turkish photographic books. Of course, the postcard captions and the history books were written by the winners, so there is nothing of the fires or the horror of the bloody harbor. Look at the black and white picture of the quay of Smyrna in 1916. I took a photo of the same general spot, which is to the right of the white Hotel Key in the previous photo. You can compare the scenes as they were in Smyrna and as they are in Izmir.

While the black and white postcard does not show the Grand Hotel Huck, you can see through a passageway from the waterfront to the parallel road behind it, a tall cupola on a corner building having five windows with gothic arches. The contemporary photo shows that the passageway, the corner building with the cupola, and the five gothic windows are still there, now under a red tiled roof. By careful triangulation, we figured out where to place Grandpa’s brasserie on the modern quay. We found there, next to parked cars and under a ten-story modern building . . . an ATM machine.

Most of the time the visual present was overwhelming. When that happened, we would turn to the hills on the other side of the Gulf of Izmir and recognize their unchanged outline. I could at least be sure that a century earlier my grandparents, my father, and my aunts and uncles saw the same hills, with the same slopes and the same valleys. I could then feel my grandparents’ presence at our side.

Ahead of our trip we hired the services of a local guide, recommended to us as an expert on the Jewish geography of Old Smyrna. I don't think, however, that she expected to guide someone who had done so much research and who wanted to see very specific things. She had a canned tour that we were not much interested in and she seemed disappointed. She wanted to show us the historic Konak Square, the Governor's Palace, and the Izmir Clock Tower. After that she would take us to several old Sephardic synagogues.

I think I threw her when I started out by asking, “OK, but can we first see the site of the Grand Hotel Huck?” She looked at me with an attitude, like, Who is this guy? When I made clear that I wasn’t particularly interested in synagogues, our relation turned even stiffer. And it was made worse after I told her the story of the Goldstein clan from Transylvania. I am sure that she then concluded that my ancestors didn’t really belong in Smyrna, not the way hers, descended from 15th century Spanish Jews, belonged. She realized that she was dealing with a descendant of Levantines, and not very religious ones. When I asked where the Levantines lived, she said, “Big villas with tall walls, but there’s nothing left of those days.” When I said I wanted to see the Rue Franque, where Grandpa Leon had apparently worked in a clothing store, she said, “It’s far.” So, we ended up not going to either. Her plan to show us all of those synagogues quickly shrunk to just two, both Sephardic. One was small, plain, and run down. It was near the local Kemeralti bazaar, a place that in the 19th century used to be a caravanserai, a lodging inn for camels and their drivers. The other synagogue turned out to be a large beautiful one in the old Jewish neighborhood of Karataş.

Yet, despite our differences, we learned a lot from her. She is a member of the ever-smaller Sephardic community. As far as she knew, there are no Ashkenazim left. Before I arrived in Izmir I was not as aware of the social distance between the Sephardic, Ashkenazi, and Levantine Jewish communities. They traded with each other but didn’t share the same synagogues and probably didn’t intermarry much. I doubt that Dad had much religion in him when he lived there. I guess that to our guide, my family was a bunch of snobbish Europeans who didn't even think of themselves as Jews. She was probably right.

From Henri Nahum’s book, Juifs de Smyrne, I learned that well-to-do Smyrna Jews lived in the Karataş neighborhood, a high quarter looking down on the bay. By the time we visited, I already doubted that the Goldsteins had lived there since it was far from the Levantine quarter and far from downtown. Karataş is twenty minutes by cab along the Mustafa Kemal Boulevard. It was when our cab climbed up the hill toward the quarter that we encountered the Asansör, that strange elevator shaft.

We rode it up and took in the view from the top. Sure enough, Dad’s ghost was at the landing when we visited. He seemed dizzy from the heat and confused by how tall the buildings had become, but he recognized the curves of the coastline, the mountains in the distance, and he smiled when he saw the old elevator shaft. We stared together at the hills across the Gulf of Izmir. Looking at them took us back to the ambitions of his youth, the ones that were so violently cut short when much of the place was burned down.

Before leaving, Sandy and I did visit Konak Square to see the Governor's Palace and the Izmir Clock Tower. The Tower was designed by a Levantine French architect and built in 1901, when Dad was seven. The clock itself was a gift from German Emperor Wilhelm II. All that Levantine, French, and German history spelled Goldsteins to me, and I wanted to see it.

***

When comparing a sepia photo of Konak Square from long ago with a colorful contemporary one, you can see that the Tower is still there and, behind it to our left, is the Governor’s Palace. Except for a palm tree or two and one high rise, the scene has not changed much in one hundred years.

While standing there I strained and, faintly, could see Dad once again. This time he was a small boy of ten. He didn’t see me. He was running into a flock of pigeons next to the Tower and laughing as they flew away in terror. He was happy, years away from the many tragedies that would change his world. To my surprise, as he was running, he turned into me. Suddenly it was I, ten-year-old Jorgito, running with joy through the noisy leaves of our old Buenos Aires neighborhood. As I was merrily running to school, I did not know that a year later Mom would die and that my own world would also change.

One more blog to tie some loose ends, and I will then tell you about Mom.

Comments